Files

Creator’s ZIP folder of all the completed files. The ‘run.py’ file is the home base where the game is played.

This is my (Grant’s) version of the same files, denoted by the ‘1’ in the names. Neither is perfect, we both have unique flaws. I recommend downloading both versions and experimenting with how the games run.

This is a ZIP folder of the codes for each milestone of the game’s creation. These are based on my version, not the creator’s. Make sure your indentations are uniform when pasting this into your IDE.

Troubleshoot tips: While the non-Python files are in the zip folder, make sure they’re also in the home base folder that the zip folder lies in. You’ll likely have to copy and paste them.

Intro & Overview

So I first did Pong as a way to practice Python outside of random exercises. I learned a little but it still left out a lot of features of the language. So to take it up a notch, I’m remaking Pacman entirely in Python. This involves every feature of the language from functions to loops, libraries, and dictionaries.

I found this amazing website pacmancode.com that walks through the process of coding the game in Python. I couldn’t find the creator’s name, but I commend him for making this. This is what educational content creation is all about: create what you wish had existed when you were starting out.

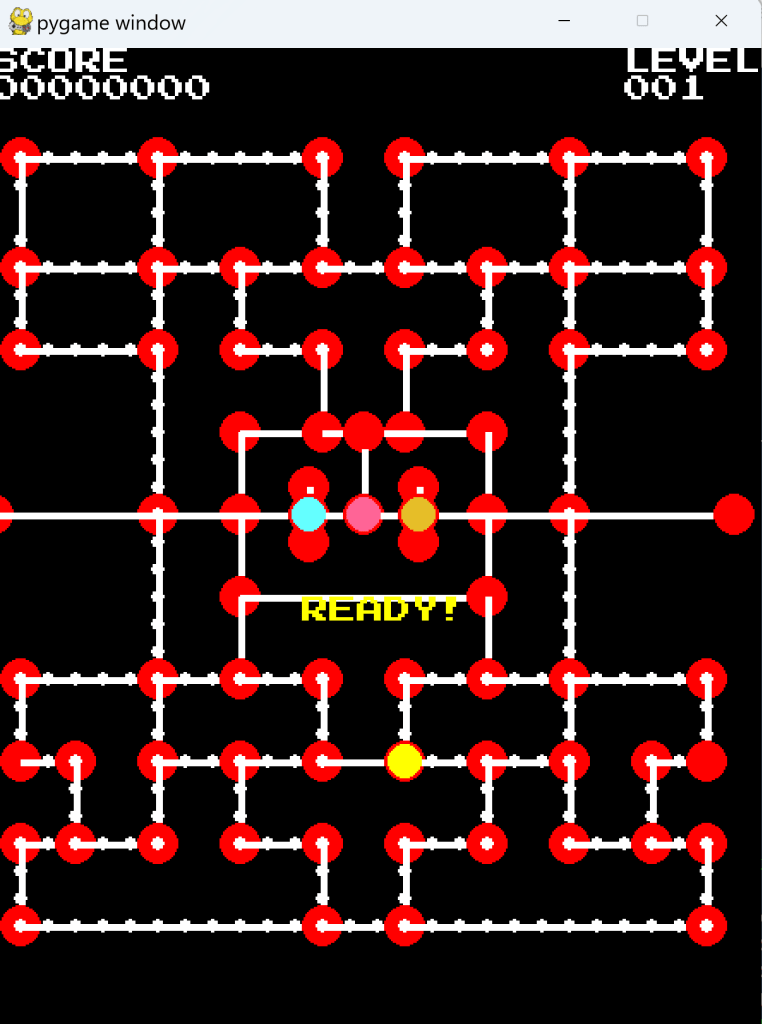

Ima be straight with yall, this isn’t perfect. It’s not fully functional arcade-ready. Even running the code the creator made still has some issues. The characters are misaligned, the button feedback is stiff, and a few other things. I just did this to get more practice in Python. I have more important things to do with it, so I wasn’t gonna spend all my time correcting each and every error. So again, this won’t be a polished version, but the base will be there. I may revise this later, but don’t take it too serious.

So first I’ll give yall an overview of the sections we’ll be going through. We’ll start with the game area, which is the maze. We’ll set up a bare-bones version of Pacman and his basic movement. Then we’ll move on to the nodes that will make up the maze. This is the most tedious part of the process. Luckily it’s in the early stages so we’re getting this out the way. Then we’ll set the features of the maze, like its borders, portals, and pellets. We’ll be connecting these features to Pacman during this part too. The hump of this project is the ghosts. We’ll spend a chunk of time on them. Creating them, setting their different chase styles, and setting the modes of the game which include Pacman eating a power pellet, followed by him eating a ghost, the short time when a ghost is eaten and rushes back to its home base, and dying from a ghost. After that, we’ll handle the auxiliary game mechanics like the character’s starting positions, the fruit, Pacman’s lives, pausing, and ending a level. One big thing I couldn’t figure out in time is reviving Pacman after he loses a life. I got his death animation down, but if he loses a life, an error pops up, and it’s too layered to focus on. So I’ll admit this is the main game-breaking flaw I had to leave in. If you’re testing this code and running the game as you follow along, don’t let him die. After that, it’s really all aesthetics from this point on. We’ll be using a pre-made sprite sheet that contains all the images from the original game. Remember some objects actually change shape instead of just moving, like Pacman’s death or the ghosts’ eyes. These are animations, which means you’ll need each frame of the object in a different state. The sprite sheet saves us time from having to create all of that from scratch.

Setup

All you need to set this up is a working computer. Download the Python language from the official site, it’s free. And you’ll only need to install 2 libraries: Pygame (obviously) and NumPy which we’ll be using to add the nodes into a data structure. To install these libraries, open your computer’s terminal, it may be called ‘command prompt’ or ‘PowerShell’, and type “pip install pygame numpy“. This will install both libraries for you. Again, this is all free and takes up little space. You’ll also need an editor to actually type the code into. I used the IDLE that comes with Python when you download it, so that’ll work for you too; just search for the ‘IDLE’ app on your computer. You don’t have to use this one, but any other one is gonna add complications if you’re not already used to it. This is the basic word doc for writing code in Python.

We’re also going to be using many separate files that’ll be imported into each other. So I suggest creating a folder to hold those files.

After going through this whole thing, I have a 3-step heuristic for how Python works: If you want to move an apple, you first have to state that there is an apple, then you have to state there are things you’d like to do with the apple, then you move the apple. Just about any error, outside of spelling or spacing, happens because one of these steps was missed. The ‘init’ method will usually hold the first step. The use of ‘self’ is for the sake of the second step in most cases, and the other methods is where the actual work is done.

Vectors

Starting off, as with any game, there’s the space of the play area. This space is a grid. To get from point A to point B, I would give you 2 sets of information: distance and direction. “Go up 3 blocks, turn right for 2 blocks, hang a left, then stay straight for 5 blocks.”

Create a file called ‘vectors’, and make sure it’s a Python file, which you can tell by it ending in ‘.py’. This first code imports a ‘math’ package to use predefined functions.

import math

class Vector2(object):

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.thresh = 0.000001x and y represent the coordinates the vector is pointing towards. As with any initialize (init) function, we start the arguments with ‘self’ and establish them with themselves using a ‘self’ reference.

The arithmetic we’ll be doing is adding and subtracting vectors along with multiplying and dividing vectors by scalars; in that order.

def __add__(self, other):

return Vector2(self.x + other.x, self.y + other.y)

def __sub__(self, other):

return Vector2(self.x - other.x, self.y - other.y)

def __neg__(self):

return Vector2(-self.x, -self.y)

def __mul__(self, scalar):

return Vector2(self.x * scalar, self.y * scalar)

def __div__(self, scalar):

if scalar != 0:

return Vector2(self.x / float(scalar), self.y / float(scalar))

return None

def __truediv__(self, scalar):

return self.__div__(scalar)For the first 2, addition and subtraction, ‘self’ is the current Vector2 instance, and ‘other’ will be whatever other number we put in the equation. The next one ‘neg’ makes the coordinates negative. The next 2 ‘mul’ and ‘div’ do their respective operations. They’re set to scalar which is standard arithmetic when dealing with vectors. The ‘div’ sets its scalars to be floating-point (allowing decimals) to ensure precision.

The regular ‘div’ is for Python 3 and the ‘truediv’ is for Python 2. Ensuring this can play on the current and previous versions.

This method checks for equality between 2 vectors. In scientific computing, 3 and 3.000001 are usually considered as different, but they can suffice as equal for this case Our ‘self.thresh’ variable is the threshold tolerance for the biggest difference the equality checker will allow. We subtract the 2 values to see if the difference is smaller than our threshold value. The ‘abs’ is what calculates the absolute value of the number it’s passed.

def __eq__(self, other):

if abs(self.x - other.x) < self.thresh:

if abs(self.y - other.y) < self.thresh:

return True

return FalseHere we have 2 magnitude methods. ‘magnitude’ returns the actual length of the vector which requires a square root (which is why we had to import the ‘math’ package). ‘magnitudeSquared’ is the method we’ll be calling throughout the game since it does the squaring for us.

def magnitudeSquared(self):

return self.x**2 + self.y**2

def magnitude(self):

return math.sqrt(self.magnitudeSquared())This string method doesn’t have any functionality for the game. It’s used to print out the vector and make it more accessible. This is for organizational purposes.

def __str__(self):

return "<"+str(self.x)+", "+str(self.y)+">"This ‘copy’ method will copy a vector so we get a new instance of it. The other 2 methods convert our vector into a tuple and an int(eger) tuple which will make the code cleaner for later.

def copy(self):

return Vector2(self.x, self.y)

def asTuple(self):

return self.x, self.y

def asInt(self):

return int(self.x), int(self.y)Blank Screen

We store all of our constants (values that don’t change) in one file we’ll call constants. Make sure it’s still a Python file too.

TILEWIDTH = 16

TILEHEIGHT = 16

NROWS = 36

NCOLS = 28

SCREENWIDTH = NCOLS*TILEWIDTH

SCREENHEIGHT = NROWS*TILEHEIGHT

SCREENSIZE = (SCREENWIDTH, SCREENHEIGHT)

BLACK = (0, 0, 0)Our next lines serve as an entry point into our game. We create a run.py file that’ll be the main one we use to run the game. Every other file will be imported into this one.

Then we create a GameController class followed by a Pygame initialization, defining the screen using the values from the constants file, and calling a method that sets up the background (which we haven’t created yet). In run.py

import pygame

from pygame.locals import *

from constants import *

class GameController(object):

def __init__(self):

pygame.init()

self.screen = pygame.display.set_mode(SCREENSIZE, 0, 32)

self.background = NoneNext we set the background color to black.

def setBackground(self):

self.background = pygame.surface.Surface(SCREENSIZE).convert()

self.background.fill(BLACK)We’re gonna set the ‘start game’ and ‘update’ methods to be used later.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

def update(self):

self.checkEvents()

self.render()Then we set the ‘checkEvents’ method for quitting the game. Without this, the X wouldn’t do anything. Yes, you have to manually tell a program that you will want to close it at some point. The ‘render’ method is to initialize the drawings we’ll be doing. In run.py

def checkEvents(self):

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == QUIT:

exit()

def render(self):

pygame.display.update()This block will be at the very bottom of the run.py file. The ‘if’ checks if the script being run is the main program. The ‘game’ variable after that creates an instance of the GameController class. Again, if you want to work with something, you have to establish it, and then tell it you want to work with it. This takes care of the second part.

The ‘game.startGame()’ calls the ‘startGame’ method on the ‘game’ object; calling it to be used. Below that is an infinite loop for the ‘update’ method that continually advances the game through whatever state it needs to.

class GameController(object):

...

if __name__ == "__main__":

game = GameController()

game.startGame()

while True:

game.update()At this point, when you run the run.py file, a blank pygame screen should pop up.

Basic Movement

This part takes a bit of physics. The equation s(Δt) = s0 + vΔt + ½*aΔt2 represents one-dimensional motion. s0 is our current position, regardless if it’s x or y. V is our velocity which is speed and direction. s(Δt) is our new position. Δt is the time it’ll take to get to this new position. a is the acceleration of an object as it’s moving towards that new position. In this case, anything that’s moving in the game is either moving at full speed or not moving at all. Acceleration entails speeding up or slowing down, which isn’t a factor in this game. That said, we can set our acceleration to 0 since it’s not involved in the mechanics. We can now cut out everything after that second plus in the equation and simplify it to s(Δt) = s0 + vΔt.

So to calculate our new position, all we need is our current position, the direction and speed we want to move in, and the time it will take to get there. That’s 3 simple variables. We’re gonna handle some timing issues later on.

Next we initialize a time clock at the end of the ‘init’ method of the GameController class. In run.py

def __init__(self)

...

self.clock = pygame.time.Clock()Next we’re adding this ‘dt’ (delta time) variable as the first line of the ‘update’ method which returns the amount of time that has passed since the last time this line was called. 30 is the frame rate. We divide it by 1000 so the result is in seconds and not milliseconds. Overall, this is the game’s time tracker. When we want to manipulate how long certain things last, like the bonus fruit or the ghosts’ vulnerability, this variable helps the game recognize the passage of time so it knows how to mark when something should occur. This is placed in the ‘update’ method since the game will continually have to do this.

The 2 bottom ‘self’ statements were already there. We’re adding the ‘dt’ variable.

def update(self):

dt = self.clock.tick(30) / 1000.0

self.checkEvents()

self.render()Next we’re defining our constants starting with Pacman’s color, he’s yellow, which is a mix of red and green. So we set those values to 255 and leave blue at 0.

YELLOW = (255, 255, 0)

STOP = 0

UP = 1

DOWN = -1

LEFT = 2

RIGHT = -2

PACMAN = 0With those in place, we can now draw the man himself. We’re creating a new file called pacman.py for this.

We import pygame of course. The ‘pygame.locals’ line is a module within Pygame that’ll recognize and operate certain keywords when we use them. The asterisk after that is to import all the properties of this module. Otherwise, when we use them, we’d have to put ‘pygame.locals’ before each one, which is tedious. This has to be manually done since Pygame is a big library with too many modules to import all at once. And of course, we import the Vector2 class from the ‘vector’ file and bring over all of the ‘constants’ file.

So we create the Pacman class. The ‘object’ argument tells the class to inherit from a base ‘object’ class. This was standard in Python 2, but automatically done in Python 3. So we could technically leave it out and have it still work.

As with any class, we start with an ‘init’ method to initialize everything. We add these instance variables that will hold the data for his characteristics. We first got his name and his initial position on the game board (which is 200, 400).

This ‘self.directions’ instance creates a dictionary that controls his movement in response to certain key presses. Pacman’s initial direction is STOP since we don’t want him moving unless we say so. In Pygame coordinates, a positive x-vector is right and a positive y-vector is down. So when we want him to move up, when we press the ‘up’ key, his y-vector is set to negative, and vice versa for the down key and moving down. The same applies to left and right.

Part 2

After that, we have a ‘self.direction’ variable that’s set to ‘STOP’. Since this is the ‘init’ method, that means initially, Pacman is stopped.

Speed and color speak for themselves. The radius means we’re making his circle 10 pixels.

In the ‘update’ method, the first line updates Pacman’s position based on his current speed and direction, while also accounting for the passage of time (dt). Again ‘self.position’ is his starting position (200, 400). The other side of the equation calculates his new position and compares it to the starting.

We then set a ‘direction’ variable to check for the key that was pressed. To which that is then set by ‘self.direction’. Essentially, ‘direction’ starts at STOP, which is nothing, yet as we go on (which is the function of the ‘update’ method), the variable updates to the respective direction of the key that was pressed.

import pygame

from pygame.locals import *

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

class Pacman(object):

def __init__(self):

self.name = PACMAN

self.position = Vector2(200, 400)

self.directions = {STOP:Vector2(), UP:Vector2(0,-1), DOWN:Vector2(0,1), LEFT:Vector2(-1,0), RIGHT:Vector2(1,0)}

self.direction = STOP

self.speed = 100

self.radius = 10

self.color = YELLOW

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

direction = self.getValidKey()

self.direction = directionWe just called the ‘getValidKey’ object. Now we have to define its entailments to check for which key the player is pressing. Each key returns the direction it corresponds to. These are all ‘True/False’ Boolean values. Whichever one turns ‘True’ is the one that is returned. If none of the keys are pressed, and Pacman hits a wall, it defaults to ‘STOP’.

def getValidKey(self):

key_pressed = pygame.key.get_pressed()

if key_pressed[K_UP]:

return UP

if key_pressed[K_DOWN]:

return DOWN

if key_pressed[K_LEFT]:

return LEFT

if key_pressed[K_RIGHT]:

return RIGHT

return STOPNow for the actual drawing. We initialize it with the ‘render’ method. The ‘self’ argument refers to Pacman himself and ‘screen’ is where we’re placing him. For the ‘p’ variable, we’re converting ‘self.position’ to integers, hence the ‘asInt’ method. We do this because coordinates are stated as floating-point numbers, meaning decimals. Converting these to integers helps us keep Pacman’s position precise. And lastly we use the ‘pygame.draw.circle’ method which, you guessed it, actually draws the circle. The ‘screen’ argument obviously puts it onto the screen. The other 3 are Pacman’s characteristics which pertain to his appearance: his color, the ‘p’ variable we just set for his position, and his radius which pertains to his size since he’s a circle.

def render(self, screen):

p = self.position.asInt()

pygame.draw.circle(screen, self.color, p, self.radius)Now that we’ve set the Pacman class, we can go back to our run.py file and implement him.

First we import him. The first ‘pacman’ is the file we just came from. The second ‘Pacman’ is the class that holds the man himself.

from pacman import Pacman We add ‘self.pacman = Pacman()’ to the ‘startGame’ method. ‘self.pacman’ will allow us to call the Pacman class where we defined his characteristics. The ‘Pacman()’ set to it is the actual class.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.pacman = Pacman()In the ‘update’ method, right under the ‘dt’ variable, we make a call to Pacman’s ‘update’ method passing in that ‘dt’ as an argument, which is its resulting value. This connects the game’s time tracker to Pacman.

def update(self):

dt = self.clock.tick(30) / 1000.0

self.pacman.update(dt)

self.checkEvents()

self.render()Lastly, we add 2 lines to our ‘render’ method. The ‘screen.blit’ line redraws the background. Otherwise any object that moves would appear to be smearing across the display. The objects need to be erased and redrawn in their new positions.

And the last ‘render’ line is the final touch to put Pacman onto the screen.

def render(self):

pygame.display.update()

self.screen.blit(self.background, (0, 0))

self.pacman.render(self.screen)At this point, we have a black screen with a yellow circle we can control with the keyboard.

Nodes

Even though we’ve given Pacman the freedom to move, we gotta add constraints so he only moves within the maze.

A node by itself is a piece of information. Its most important trait is its position. 2 nodes that are directly linked are considered neighbors. They’re connected by a path. A collection of connected nodes is a map. The maps in this game will only have up to 4 nodes since Pacman can only move in 4 directions. Also note that a node can only have one neighbor per direction.

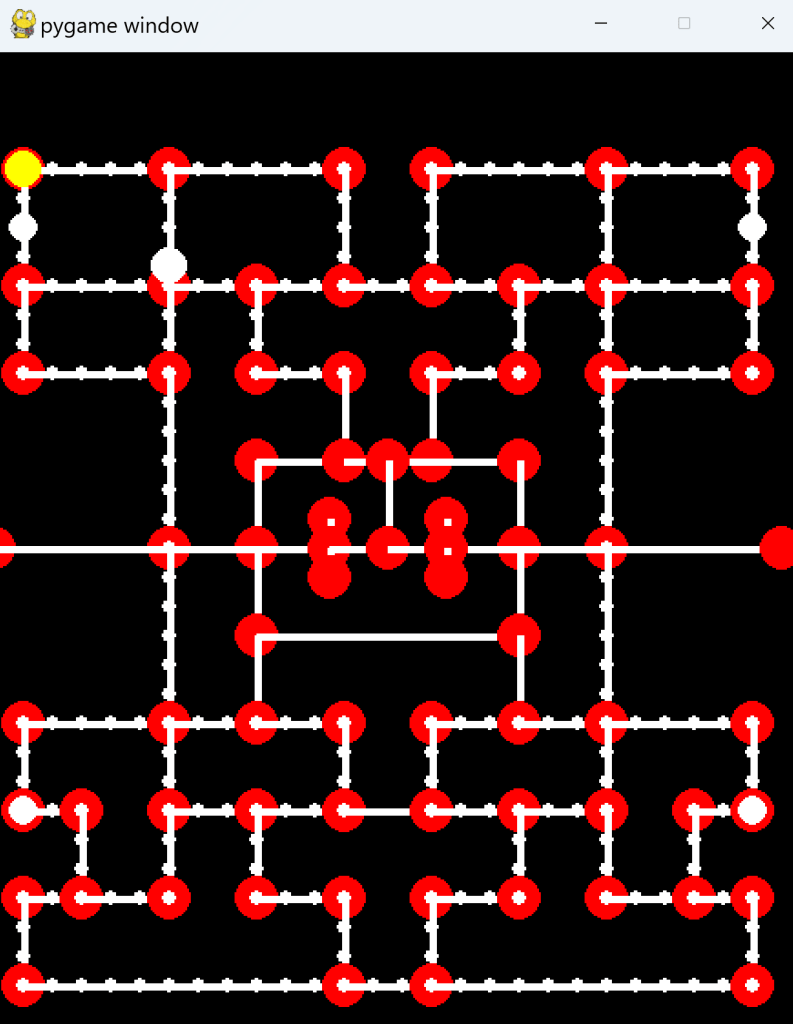

These are a set of 7 nodes labeled A-G on a grid. We see that node A has 2 neighbors, B and C. Node D has 3 neighbors, B, C, and E. We identify their position by the numbers on the edge.

We’ll add white and red with their RGB values to our constants.py file which will represent the lines connecting the nodes.

WHITE = (255, 255, 255)

RED = (255, 0, 0)We’re also creating a separate node file and adding a ‘node’ class. As always we first import pygame. Then import the ‘Vector2’ class and the ‘constants’ file.

As always, we start a new feature with an ‘init’ method to initialize it. It takes the arguments ‘self’ (which is a given), and x & y to specify the node’s position. The next ‘self.position’ does this again to solidify that the nodes will have a position. The next ‘self.neighbors’ line creates a dictionary with all directions. They’re all set to ‘None’ to state that no node has neighbors when it’s first.

The ‘render’ method is what’ll draw the nodes. It takes the arguments ‘self’ and ‘screen’; same function as it was used for making the Pacman character. The ‘for’ loop is set to iterate through all the keys of the ‘self.neighbors’ dictionary we just set; the 4 directions. The ‘.keys()’ is a method call to access the keys in a dictionary. Per the second line, each iteration checks if the neighbor in the current direction is not ‘None’. If it’s not, that means there’s a neighboring node in that direction. The [n] represents whichever key is the current iteration.

The ‘line_start & end’ variables mark the points of the current node for the start and the neighboring node in the current direction for the end. They’re both converted to tuples since Pygame expects coordinates in tuple form.

The 2 ‘draw’ functions at the end draw the white node circles and the red path lines.

import pygame

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

class Node(object):

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.position = Vector2(x, y)

self.neighbors = {UP:None, DOWN:None, LEFT:None, RIGHT:None}

def render(self, screen):

for n in self.neighbors.keys():

if self.neighbors[n] is not None:

line_start = self.position.asTuple()

line_end = self.neighbors[n].position.asTuple()

pygame.draw.line(screen, WHITE, line_start, line_end, 4)

pygame.draw.circle(screen, RED, self.position.asInt(), 12)Since we’re dealing with a lot of nodes, we’ll make another class called ‘NodeGroup’. All node objects will be kept in a list.

We create the class then create a method ‘setupTestNodes’ to demonstrate how we can manually link the nodes. Each node needs to have its location set upon creation. After that, we link them together adding nodes to the neighbors’ dictionary of each node. Finally, we add all of the nodes to the ‘nodeList’.

When we want to draw all of the nodes we call the ‘render’ method which just loops through the ‘nodeList’ and calls that node’s ‘render’ method.

class NodeGroup(object):

def __init__(self):

self.nodeList = []

def setupTestNodes(self):

nodeA = Node(80 ,80)

nodeB = Node(160, 80)

nodeC = Node(80, 160)

nodeD = Node(160, 160)

nodeE = Node(208, 160)

nodeF = Node(80, 320)

nodeG = Node(208, 320)

nodeA.neighbors[RIGHT] = nodeB

nodeA.neighbors[DOWN] = nodeC

nodeB.neighbors[LEFT] = nodeA

nodeB.neighbors[DOWN] = nodeD

nodeC.neighbors[UP] = nodeA

nodeC.neighbors[RIGHT] = nodeD

nodeC.neighbors[DOWN] = nodeF

nodeD.neighbors[UP] = nodeB

nodeD.neighbors[LEFT] = nodeC

nodeD.neighbors[RIGHT] = nodeE

nodeE.neighbors[LEFT] = nodeD

nodeE.neighbors[DOWN] = nodeG

nodeF.neighbors[UP] = nodeC

nodeF.neighbors[RIGHT] = nodeG

nodeG.neighbors[UP] = nodeE

nodeG.neighbors[LEFT] = nodeF

self.nodeList = [nodeA, nodeB, nodeC, nodeD, nodeE, nodeF, nodeG]

def render(self, screen):

for node in self.nodeList:

node.render(screen)Now that we have the NodeGroup class written we can create an instance of it in the GameController class back in the run.py file. First import the ‘NodeGroup’ class.

In the ‘startGame’ method we add 2 lines. The first is creating an instance of the ‘NodeGroup()’ class setting it to a variable named ‘self.nodes’. The second line uses that exact variable and calls the ‘setupTestNodes()’ method for it to perform.

The nodes line in the ‘render’ method is the final touch to put them on the screen. The same as we did with Pacman.

from nodes import NodeGroup

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.nodes = NodeGroup()

self.nodes.setupTestNodes()

self.pacman = Pacman()

def render(self):

self.screen.blit(self.background, (0,0))

self.nodes.render(self.screen)

self.pacman.render(self.screen)

pygame.display.update()

At this point, we have a fixed map of nodes along with our mouthless Pacman. He does not yet have any connection to the nodes. They’re a part of the background at this point.

Node Movement I

We have to go through 3 types of node movement. The first is simply having Pacman jump from one to the other with no transition. If node A has node B as its left neighbor, and the player presses the left key, Pacman will jump from A to B.

We have to pass in the list of nodes that make up the maze. Pacman needs his starting node to be defined. So we’ll just set his position to the first node for now.

So in the pacman.py file, we add ‘node’ as a second argument of the ‘init’ class. We add 2 more ‘self’ lines after color. ‘self.node’ set to ‘node’ initializes Pacman’s position to the node. ‘setPosition()’ does the actual tying to it.

Delete the ‘self.position’ line from the ‘init’ and ‘update’ methods.

Then we add a separate ‘setPosition’ method just before the ‘update’ method, which copies the node’s position to Pacman’s. The ‘copy’ method is used to set an independent copy of the node’s position. Without this, modifying ‘setPosition’ would modify Pacman’s position.

def __init__(self, node):

self.name = PACMAN

self.directions = {STOP:Vector2(), UP:Vector2(0,-1), DOWN:Vector2(0,1), LEFT:Vector2(-1,0), RIGHT:Vector2(1,0)}

self.direction = STOP

self.speed = 100

self.radius = 10

self.color = YELLOW

self.node = node

self.setPosition()

def setPosition(self):

self.position = self.node.position.copy()We add 2 more lines to the ‘update’ method.

The other two new methods, ‘validDirection’ and ‘getNewTarget’, check whether the key we’re pressing is a valid direction and whether there is a node in that direction. If so, then we move Pacman to that node automatically.

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

direction = self.getValidKey()

self.direction = direction

self.node = self.getNewTarget(direction)

self.setPosition()

def validDirection(self, direction):

if direction is not STOP:

if self.node.neighbors[direction] is not None:

return True

return False

def getNewTarget(self, direction):

if self.validDirection(direction):

return self.node.neighbors[direction]

return self.nodeNext in the run.py file, we modify the ‘startGame’ method so that we pass in the node we want Pacman to start on.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.nodes = NodeGroup()

self.nodes.setupTestNodes()

self.pacman = Pacman(self.nodes.nodeList[0])At this point, Pacman is now jumping from node to node only using the path to transition. He does not stay between nodes.

Part 2

So far we got Pacman jumping from node to node, but we want to see him moving between the nodes. In this part, he’ll be stopping on each node, even if a key is pressed. While Pacman is between nodes, any other key presses won’t be responsive. We also have to add a STOP condition when he starts to overshoot a node.

We’re adding a new ‘overshotTarget’ method in the pacman.py file that checks if he overshot a node. The ‘if’ loop is the lines that does this with ‘selfTarget’. If it is None, that means there is no target position to compare it with, indicating no overshot, to which it defaults to return False. If ‘selfTarget’ is not None, that means Pacman has overshot his target node. When this happens, the 2 vectors variables are calculated. ‘vec1’ finds the difference from the target position to the current node. ‘vec2’ finds the difference from Pacman’s position (self.position) to the current node. The ‘magnitudeSquared’ method is used to avoid a square root since we’re just comparing 2 distances; it simplifies the numbers.

If Pacman’s distance is greater than or equal to the distance between the 2 nodes, then he has officially overshot the target node.

def overshotTarget(self):

if self.target is not None:

vec1 = self.target.position - self.node.position

vec2 = self.position - self.node.position

node2Target = vec1.magnitudeSquared()

node2Self = vec2.magnitudeSquared()

return node2Self >= node2Target

return FalseNext we’re adding another variable to the ‘init’ method. ‘Self.target’ which is set to ‘node’. The target node is usually the node Pacman needs to move towards, but if Pacman is stationary on a node then the target node is simply None since he has no target.

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.setPosition()

self.target = nodeIn the ‘update’ method, we delete everything below the ‘direction’ variable and replace it with:

def update(self, dt):

...

if self.overshotTarget():

self.node = self.target

self.target = self.getNewTarget(direction)

if self.target is not self.node:

self.direction = direction

else:

self.direction = STOP

self.setPosition()At this point, Pacman now moves smoothly along the path between nodes. No more ‘jumping’

Part 3

Though we’ve seen Pacman move smoothly between nodes, he stops on each node. We also can’t change his direction when he’s traveling between nodes. In this section, we’ll change his movement so that he’ll only stop on a node if he can’t continue on to another node in the direction he is moving. Otherwise he’ll move past the node. We’ll also make it so he can reverse direction. By the end of this section, Pacman’s movement will be completed. It will function the same regardless of what maze you put him in.

We’re gonna create 2 new methods for the Pacman class. The first is ‘reverseDirection’. Whatever direction he’s already moving in, if I press a key of a different direction, it’ll multiply that value by -1, which makes it opposite. If LEFT is 2, pressing RIGHT makes that -2. The same goes for UP being 1 and pressing DOWN makes that -1. This is what the first ‘self.direction’ line does. The ‘temp’ variable temporarily stores ‘self.node’ so its value can be swapped with ‘self.target’s in the next line. Then in the line after that, ‘self.target’ takes the value of ‘temp’ which solidifies the swap.

But once we move Pacman in the opposite direction, we still have to swap the node and target, which leads to our second method.

‘oppositeDirection’ checks if the input direction is the opposite of Pacman’s current direction. The reason I want to check for this is because when Pacman is moving between nodes, the only direction he can move in is his current direction and his opposite direction. If he’s going left, he can either keep going that way, or go right. He shouldn’t be able to move up or down while he’s on that path. So I want to make sure that the input is a valid direction before saying he can move in that direction.

The ‘if’ loop states if the ‘direction’ argument is not ‘STOP’ it checks the condition that ‘direction’ is equal to the opposite of the current direction. So if the current direction (self.direction) is 2, and the ‘direction’ argument is -2, then they’re equal in that case thus it’ll return True.

def reverseDirection(self):

self.direction *= -1

temp = self.node

self.node = self.target

self.target = temp

def oppositeDirection(self, direction):

if direction is not STOP:

if direction == self.direction * -1:

return True

return False Lastly for this section we’re modifying the ‘update’ method. If the input direction does not get us a new valid target, then we check the current direction Pacman is moving in.

Remove the 2 lines under the ‘else’ and replace it with a ‘self.target’ variable set to the ‘getNewTarget’ object and including the direction. The new ‘if’ statement ensures that Pacman will stop when he hits a wall. Since he continuously moves forward, his target node can only be the same as his current one if he can’t move any more forward; which means he hit a wall. The last ‘else’ statement operates his reverse direction.

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

direction = self.getValidKey()

if self.overshotTarget():

self.node = self.target

self.target = self.getNewTarget(direction)

if self.target is not self.node:

self.direction = direction

else:

self.target = self.getNewTarget(self.direction)

if self.target is self.node:

self.direction = STOP

self.setPosition()

else:

if self.oppositeDirection(direction):

self.reverseDirection()At this point, Pacman can now reverse direction while he’s traveling between nodes.

Maze Basics

Life is short. We don’t have time to create the maze node by node. So we’re gonna generate it automatically. To do this, we’ll create a text file, use that file as an input for some method, and then have that method output the required ‘nodeList’. To keep the file simple, we’ll create a small system of symbols to illustrate nodes and empty spaces for the computer to read.

- “X”: empty space

- “+”: node

- “.”: vertical/horizontal path (connectors)

We’re gonna use the map and add it into the text file. Again, make sure it’s a TEXT file (.txt) and not a Python one.

X X X X X X X X

X + . . + X X X

X . X X . X X X

X + . . + . + X

X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X

X + . . . . + X

X X X X X X X XIn the node.py file, we’re first gonna import NumPy.

Add ‘level’ as an argument to the ‘init’ method of ‘NodeGroup’. We’re also gonna delete the ‘setupTestNode’ method. Now on to the additions to the ‘init’ method.

Delete ‘setupTestNodes’ and the ‘self.nodeList’ from ‘init’.

Since we imported Numpy, this will read out the text file and put it into an array, which we then transpose. We want the text file to be read in when we create an object from this class.

We take the ‘level’ argument and assign it to ‘self.level’ to create its own instance. ‘self.nodeLUT’ creates an empty dictionary for the lookup table. The 2 ‘symbol’ lines set the symbols, as you’d expect. We’re also storing our symbols in a list since we’ll need other symbols for other nodes and paths. The ‘data’ variable is set to read the maze file, as the method is named. It also calls ‘level’ as an argument or else it wouldn’t connect. The last 3 lines with the ‘data’ argument (that we literally just made) are the remaining steps for generating the maze.

import pygame

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

import numpy as np

class NodeGroup(object):

def __init__(self, level):

self.level = level

self.nodesLUT = {}

self.nodeSymbols = ['+']

self.pathSymbols = ['.']

data = self.readMazeFile(level)

self.createNodeTable(data)

self.connectHorizontally(data)

self.connectVertically(data)This next method is the text file using NumPy’s ‘loadtxt’ function, hence the ‘np’. The dtype needs to be set to ‘<U1’ or else it will try to read in the data as floats and create an error when it encounters non-float characters like the ‘.’ character. This will return a 2D NumPy array.

def readMazeFile(self, textfile):

return np.loadtxt(textfile, dtype='<U1')Now we’re creating the node table as a NumPy 2D array data structure. We’ll go through it row by row, and whenever we find a ‘+’, we’ll create an entry in the lookup table with the row and column the node was found in and create a Node object. The ‘data’ argument represents the array. It’s not built-in but ‘data’ is the common name we give to structures like that. The ‘offsets’ are meant to adjust the position of the coordinates by spacing them from the margin, but since they’re set to 0, they’re moot.

We start with a ‘for’ loop that iterates over the rows in the maze array. The ‘.shape’ method after ‘data’ is a NumPy attribute that collects the dimensions of an array. The [0] after that targets the rows of the array. [1] would be the columns. The ‘data.shape’ is within a ‘range’ function which will tell us how many rows there are. The ‘list’ function converts the range to a list.

We make these 2 loops for the rows and columns. The ‘if’ statement after that checks that the values of the (row, col) position are present in the ‘self.nodeSymbols’ list; it’s looking for a node. If the values are there, it calls the ‘constructKey’ method that converts a row and column in a text file to actual pixel values on the screen by multiplying them by whatever values we set for the tile sizes.

So the dictionary keys will be a (x,y) tuple, then the values will be a Node object. We’ll pass in the (x,y) location to that Node object as well. The dictionary makes it easier to lookup a node with its (x, y) position. If we only had a list of the node objects, we’d have to loop through them just to find a specific node.

def createNodeTable(self, data, xoffset=0, yoffset=0):

for row in list(range(data.shape[0])):

for col in list(range(data.shape[1])):

if data[row][col] in self.nodeSymbols:

x, y = self.constructKey(col+xoffset, row+yoffset)

self.nodesLUT[(x, y)] = Node(x, y)

def constructKey(self, x, y):

return x * TILEWIDTH, y * TILEHEIGHTConnecting Nodes Horizontally & Vertically

At this point we have a dictionary of Node objects, but none of the nodes are connected together. We’re gonna follow a 2-step process to connect them. Horizontally, then vertically.

When making the method, we use the same arguments we used in ‘createNodeTable’. Remember ‘data’ is the array of the maze symbols. The 2 ‘for’ loops do the same thing as they did in the last one: iterate through each row and column.

The ‘if’ statement checks if the current iterated position is in the ‘self.nodeSymbols’ set.

We scan each row for a ‘+’. When we find one, we check if the ‘key’ value is ‘None’ or not. We initially set it to ‘None’ when we start on a new row. The key can also contain a key to our dictionary. We call it ‘key’ so we know if 2 nodes need to be connected horizontally or not.

Again, when we come across a key, we look at the value of the key variable. If its value is ‘None’, we set it to the key of that node in the dictionary. This way we can see if it connects to another node down the line.

If we encounter a ‘+’ that is not None, but an actual value, then we connect those 2 nodes. Since we’re moving left to right, the new node we encountered is to the right of the previous node we encountered. And the previous node is to the left of the new node. Anytime we encounter any characters that are not in the ‘pathSymbols‘ list (which only contains ‘.’ for now), then set the key to ‘None‘ again.

def connectHorizontally(self, data, xoffset=0, yoffset=0):

for row in list(range(data.shape[0])):

key = None

for col in list(range(data.shape[1])):

if data[row][col] in self.nodeSymbols:

if key is None:

key = self.constructKey(col+xoffset, row+yoffset)

else:

otherkey = self.constructKey(col+xoffset, row+yoffset)

self.nodesLUT[key].neighbors[RIGHT] = self.nodesLUT[otherkey]

self.nodesLUT[otherkey].neighbors[LEFT] = self.nodesLUT[key]

key = otherkey

elif data[row][col] not in self.pathSymbols:

key = NoneTo connect them vertically, we’re gonna transpose the array. Which means the columns become rows and the rows become columns. This way we can apply the same logic we just did to connecting the nodes vertically. The main difference here is when we connect the nodes we need to reference UP and DOWN instead of LEFT and RIGHT. If we have an array that has shape (m, n), then the shape of the transposed array is (n, m). Other than that, the code is pretty much the same.

The ‘dataT’ is the variable we’re setting for the transposed version of the array. After that, the process is the same as horizontal. Just apply ‘dataT’ where ‘data’ would be.

def connectVertically(self, data, xoffset=0, yoffset=0):

dataT = data.transpose()

for col in list(range(dataT.shape[0])):

key = None

for row in list(range(dataT.shape[1])):

if dataT[col][row] in self.nodeSymbols:

if key is None:

key = self.constructKey(col+xoffset, row+yoffset)

else:

otherkey = self.constructKey(col+xoffset, row+yoffset)

self.nodesLUT[key].neighbors[DOWN] = self.nodesLUT[otherkey]

self.nodesLUT[otherkey].neighbors[UP] = self.nodesLUT[key]

key = otherkey

elif dataT[col][row] not in self.pathSymbols:

key = NoneWe’re also adding 2 methods that allow us to access a node through its pixel location (x, y) or its tile location (row, column).

def getNodeFromPixels(self, xpixel, ypixel):

if (xpixel, ypixel) in self.nodesLUT.keys():

return self.nodesLUT[(xpixel, ypixel)]

return None

def getNodeFromTiles(self, col, row):

x, y = self.constructKey(col, row)

if (x, y) in self.nodesLUT.keys():

return self.nodesLUT[(x, y)]

return NoneNext we’ll add a temporary ‘start node’ method. For now it’ll be the first node in the lookup table. We’ll change it later.

def getStartTempNode(self):

nodes = list(self.nodesLUT.values())

return nodes[0]Next we have to change how to reference the nodes for drawing to the screen since we’re using the nodesLUT instead of the nodesList to keep track of our nodes.

Delete the ‘self.nodeList’ method and replace it with the LUT

def render(self, screen):

for node in self.nodesLUT.values():

node.render(screen)Lastly we have to modify the ‘startGame’ method in the GameController class by passing in the name of the text file when we create the NodeGroup object. This is done in the run.py file.

Add “mazetest.txt” as an argument to the first ‘self.nodes’ line. Delete the second ‘self.nodes’. In ‘self.pacman’, delete the ‘nodeList[0]’ method, and replace that with ‘getStartTempNode()’

Then for the Pacman object we’ll call the method we just created that will return the node Pacman should start on.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.nodes = NodeGroup("mazetest.txt")

self.pacman = Pacman(self.nodes.getStartTempNode())Maze 1

We’re gonna scrap that test maze and add in a real one that we can play on. It won’t have graphics but the layout will be there. Name it ‘maze1.txt‘

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X + . . . . + . . . . . + X X + . . . . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X + . . . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X . X

X + . . . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . . . + X

X X X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X + . . + . . + . . + X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X . X X X = = X X X . X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X

+ . . . . . + . . + X X X X X X X X + . . + . . . . . +

X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X + . . . . . . . . + X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X

X + . . . . + . . + . . + X X + . . + . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X + . + X X + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + X X + . + X

X X X . X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X . X X X

X X X . X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X . X X X

X + . + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + . + X

X . X X X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X X X . X

X . X X X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X X X . X

X + . . . . . . . . . . + . . + . . . . . . . . . . + X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XGo back to the ‘GameController’ class in the run.py file and change the maze file name in ‘self.nodes’.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.nodes = NodeGroup("maze1.txt")

self.pacman = Pacman(self.nodes.getStartTempNode())At this point, Pacman has a full maze he can move through. The portals don’t yet go anywhere, so he just stops.

Portals

A signature feature of Pacman is the portals that take you from one side of the maze to the other.

To make this, we’re gonna add a new neighbor type next to our regular directional ones. This neighbor will let us jump (or portal) to it. Add ‘PORTAL’ after ‘RIGHT’ and set it to ‘None’ like the others.

class Node(object):

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.position = Vector2D(x, y)

self.neighbors = {UP:None, DOWN:None, LEFT:None, RIGHT:None, PORTAL:None}We’ll also add PORTAL to the ‘constants.py‘ file. Its value is irrelevant, so we’ll just put 3.

PORTAL = 3Obviously, the portals have to be in pairs. Otherwise where would Pacman go? So we’re gonna create a new method in the ‘NodeGroup’ class that takes 2 tuple values that’ll check if they’re in the nodes’ LUT or not.

The 2 ‘key’ variables create a key for their respective pairs. The asterisk (*) in front of the ‘pair’ argument unpacks all the elements of ‘pair’s arguments, which is x and y. The ‘if’ statement after the keys checks if they’re present in the LUT. If they’re not, we move on. If they are, we connect them with the PORTAL key which is what the last 2 lines take care of.

def setupPortalPair(self, pair1, pair2):

key1 = self.constructKey(*pair1)

key2 = self.constructKey(*pair2)

if key1 in self.nodesLUT.keys() and key2 in self.nodesLUT.keys():

self.nodesLUT[key1].neighbors[PORTAL] = self.nodesLUT[key2]

self.nodesLUT[key2].neighbors[PORTAL] = self.nodesLUT[key1]In the GameController class in run.py we have to call this new method after creating the node object. 2 tuples of 2 nodes to be connected are passed in. There’s no particular reason we chose these values, we just need something in there for now.

def startGame(self):

self.setBackground()

self.nodes = NodeGroup("maze1.txt")

self.nodes.setPortalPair((0,17), (27,17))

self.pacman = Pacman(self.nodes.getStartTempNode())Now we have to tell Pacman to jump from one node to another when going through a portal. When Pacman overshoots a node we set that node as his current node and then find the next target node. Before we try to find the next target node, we check to see if this new node is a portal node or not. If not, then we move on like normal. If it is, then we set that node’s portal node as the new node instead. In the ‘update’ method of pacman.py

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

direction = self.getValidKey()

if self.overshotTarget():

self.node = self.target

if self.node.neighbors[PORTAL] is not None:

self.node = self.node.neighbors[PORTAL]

self.target = self.getNewTarget(direction)

if self.target is not self.node:

self.direction = direction

else:

self.target = self.getNewTarget(self.direction)

if self.target is self.node:

self.direction = STOP

self.setPosition()

else:

if self.oppositeDirection(direction):

self.reverseDirection()Pacman can now go through a portal and come out the other with no issue

Pellets

In the original Pacman, there were 240 regular pellets plus 4 power pellets in each level. Regular is worth 10 points and power is worth 50, giving you 2600 points minimum for eating all the pellets in the level.

We’ll be following this based on our maze symbols:

- Anywhere there’s a ‘.’ or a ‘+’, place a pellet.

- Anywhere there’s a ‘p’, place a power pellet

- Anywhere there’s a ‘P’, place a power pellet

‘p’ is for a path and ‘P’ is for a node. We’ll also need symbols for areas with no pellets

- Anywhere there’s a ‘+’, ‘P’, ‘n’, place a node

- Anywhere there’s a ‘.’, ‘-‘, ‘|’, ‘p’, place a path

We’ll modify our maze.txt file and place pellets into it:

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X + . . . . + . . . . . + X X + . . . . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X p X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X p X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X + . . . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X . X

X + . . . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . . . + X

X X X X X X . X X X X X | X X | X X X X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X X X X | X X | X X X X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X n - - n - - n - - n X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X | X X X = = X X X | X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X | X X X X X X X X | X X . X X X X X X

n - - - - - + - - n X X X X X X X X n - - + - - - - - n

X X X X X X . X X | X X X X X X X X | X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X | X X X X X X X X | X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X n - - - - - - - - n X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X | X X X X X X X X | X X . X X X X X X

X X X X X X . X X | X X X X X X X X | X X . X X X X X X

X + . . . . + . . + . . + X X + . . + . . + . . . . + X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X . X X X X . X X X X X . X X . X X X X X . X X X X . X

X P . + X X + . . + . . + . . + . . + . . + X X + . P X

X X X . X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X . X X X

X X X . X X . X X . X X X X X X X X . X X . X X . X X X

X + . + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + X X + . . + . + X

X . X X X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X X X . X

X . X X X X X X X X X X . X X . X X X X X X X X X X . X

X + . . . . . . . . . . + . . + . . . . . . . . . . + X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XNow we’re gonna create a class to deal with these pellets in a new file: pellets.py.

First, we’ll add these 2 constants in our constants.py file

PACMAN = 0

PELLET = 1

POWERPELLET = 2Then add this to the new pellets.py file.

import pygame

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

import numpy as np

class Pellet(object):

def __init__(self, row, column):

self.name = PELLET

self.position = Vector2(column*TILEWIDTH, row*TILEHEIGHT)

self.color = WHITE

self.radius = int(4 * TILEWIDTH / 16)

self.collideRadius = int(4 * TILEWIDTH / 16)

self.points = 10

self.visible = True

def render(self, screen):

if self.visible:

p = self.position.asInt()

pygame.draw.circle(screen, self.color, p, self.radius)‘Self.position’ calculates a pellet’s position with the Vector2 object by multiplying its ‘row’ and ‘column’ parameters by their opposite tiles. A pellet is just a white circle that has a radius of 4 pixels. The ‘radius’ and the ‘collideRadius’ variables are multiplied by 4 then divided by 16 for the purpose of scaling the game based on the size of the display it’s being played on. It ensures that pellets are always a 16th of the tile. We also specify how many points a pellet is worth: 10 points. The ‘visible’ variable just allows us to hide a pellet if we want.

The ‘p’ variable in the ‘render’ method turns the pellet’s position to an integer.

The PowerPellet class defines the larger pellet that gives Pacman the special power to eat the ghosts. For now, the only difference is that it’s larger, it’s worth more points than the regular pellet, and it has a timer

The ‘flashTime’ variable makes the power pellet continually appear and disappear (hence ‘flash’) for a .2-second period. In the ‘update’ method, we first set the timer to ‘dt’ to keep track of the game time along with the power pellet’s flash time. The rest of the lines basically model the cycle of the flash.

class PowerPellet(Pellet):

def __init__(self, row, column):

Pellet.__init__(self, row, column)

self.name = POWERPELLET

self.radius = int(8 * TILEWIDTH / 16)

self.points = 50

self.flashTime = 0.2

self.timer = 0

def update(self, dt):

self.timer += dt

if self.timer >= self.flashTime:

self.visible = not self.visible

self.timer = 0There’s gonna be a lot of pellets on the screen, so we should keep them organized. We won’t have to call our ‘Pellet’ and ‘PowerPellet’ classes directly, they’ll be called through this class; similar to the NodeGroup that groups all the pellets into one list.

To create a pellet, we’ll read the file line by line and create a pellet at that position based on the symbol we defined earlier. Then when we want to draw them, we just call this ‘render’ method and it will take care of drawing the pellets for us.

The ‘pelletList’ just stores all of the pellets including the power pellets, and the ‘powerpellets’ list just stores the Power Pellets. The powers have their own list so we can directly access them when creating the function to make them flash.

We’re also adding an ‘isEmpty’ method that checks for when the pelletList is empty, meaning the level has been cleared. pellets.py

class PelletGroup(object):

def __init__(self, pelletfile):

self.pelletList = []

self.powerpellets = []

self.createPelletList(pelletfile)

self.numEaten = 0

def update(self, dt):

for powerpellet in self.powerpellets:

powerpellet.update(dt)

def createPelletList(self, pelletfile):

data = self.readPelletfile(pelletfile)

for row in range(data.shape[0]):

for col in range(data.shape[1]):

if data[row][col] in ['.', '+']:

self.pelletList.append(Pellet(row, col))

elif data[row][col] in ['P', 'p']:

pp = PowerPellet(row, col)

self.pelletList.append(pp)

self.powerpellets.append(pp)

def readPelletfile(self, textfile):

return np.loadtxt(textfile, dtype='<U1')

def isEmpty(self):

if len(self.pelletList) == 0:

return True

return False

def render(self, screen):

for pellet in self.pelletList:

pellet.render(screen)Next we’re gonna add some node and path symbols to reflect our new maze.txt file. We’re adding ‘P’ and ‘n’ to the node, and ‘-‘, ‘/’, and ‘p’ to the path. nodes.py

class NodeGroup(object):

def __init__(self, level):

self.level = level

self.nodesLUT = {}

self.nodeSymbols = ['+', 'P', 'n']

self.pathSymbols = ['.', '-', '|', 'p']Now for some GameController changes. In the run.py file, we’ll import the PelletGroup class we just made.

In the ‘startGame’ method we’ll create a PelletGroup object and pass in the maze1.txt file so that it will know where to create the pellets.

In the ‘render’ method we’ll draw the pellets. Draw them before drawing Pacman so that the pellets appear below Pacman.

import pygame

...

from pellets import PelletGroup

def startGame(self):

...

self.pellets = PelletGroup("maze1.txt")

def update(self):

...

self.pellets.update(dt)

def render(self):

...

self.pellets.render(self.screen)Eating Pellets

Now that we’ve got the pellets to show, we gotta make Pacman eat them. ‘Eating’ in the technical sense means he’s colliding with the pellets. To manage this, we’ll be using a circle-to-circle collision check. Let’s say we have circles A and B. They both have their own radius, RA and RB. We also have another variable, D, the actual distance between the circles. If D is greater than the sum of the radii, then the circles can’t be colliding. If D is less than or equal to the sum, then they are colliding.

In the ‘init’ method of pacman.py, we’re going to add a variable to define Pacman’s collision radius. We could set this radius to be the same as Pacman’s but we’re gonna shrink it a bit so it looks like the pellets are being ingested and not just disappearing as soon as he touches it.

class Pacman(object):

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.collideRadius = 5We’re also gonna create a new method that takes the pellet list and loops through each pellet until we find one that Pacman is colliding with. If we find the pellet he’s colliding with, we return it. If not, we return None.

Notice that we are comparing the square of the distances rather than the actual distances. This is to avoid taking the square root which is an expensive operation. Comparing the square of the distances is just as valid and faster.

def eatPellets(self, pelletList):

for pellet in pelletList:

d = self.position - pellet.position

dSquared = d.magnitudeSquared()

rSquared = (pellet.radius+self.collideRadius)**2

if dSquared <= rSquared:

return pellet

return NoneNext we’re creating a method that handles all of the pellet events. We’re sending the ‘pelletList’ to Pacman and returns the pellet (if any) that he’s colliding with. If the pellet variable is anything other than None, then we just remove that pellet from the list. This goes in the GameController class of run.py

def checkPelletEvents(self):

pellet = self.pacman.eatPellets(self.pellets.pelletList)

if pellet:

self.pellets.numEaten += 1

self.pellets.pelletList.remove(pellet)We then call it in the ‘update’ method to bring it to life

def update(self):

...

self.pellets.update(dt)

self.checkPelletEvents()

self.checkEvents()

...At this point, the pellets are in the maze and Pacman eats them. Nothing happens when a power pellet is eaten besides it disappearing.

Ghosts Intro

As we know, there are 4 unique ghosts in Pacman. Let’s look at their movement first.

They move node to node the same way Pacman does. We have to establish some principles for their movement.

- When traveling from one node to another, they can’t reverse direction (except in a few special cases)

- When a ghost gets to a node, it can move in any direction except the one it just came from. If it moved left to get to a node, it can’t then go right

- A ghost can only backtrack if it reaches a dead end.

- Ghosts move entirely on their own. The player has 0 control.

- The ghosts choose a direction when entering a node based on which direction will get them closer to the goal they are trying to reach.

We’re gonna create a new entity.py file. Since Pacman and the ghosts move similarly, we can use this generic class to set those terms along with some more specific ones. Any object that inherits from this class will be able to move around on its own. Note the ‘visible’ variable that allows any object to be made invisible.

Most of the ‘init’ method speaks for itself. The ‘setSpeed’ method may look weird and you may be asking why are we setting the speed based on the TILEWIDTH? Well, if you have a set speed like 100, that works well for a map that has 16×16 tiles. If you make the maze bigger with 32×32 tiles, for example, then Pacman will actually appear to move slower. He’s still moving at the same speed, but he has more ground to cover on a larger maze. If you make the maze with 8×8 tiles, then he’ll appear to move twice as fast. So we need to adjust his speed depending on the size of the maze so we can get a similar experience no matter how large the maze is.

The ‘setPosition’ just matches the entity’s position to the current node’s. Just how we defined those principles for the ghosts’ movement, ‘validDirection’ checks if the direction is valid for an entity to move in; returning ‘True’ if it is and leads to a neighboring node, otherwise returning ‘False’. This leads to the ‘getNewTarget’ method since the entity needs a new target node once it’s given a new direction. ‘overshotTarget’ checks for what it is. It only has those extra lines since it’s calculating the squared distance. For the ‘reverse’ and ‘oppositeDirection’ methods, the former actually changes the entity’s movement, the latter is more for A.I. purposes where it’s just checking the opposite direction in case it may be better for its goal. We just went over ‘setSpeed’. And ‘render’, as always, does the drawing.

import pygame

from pygame.locals import *

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

from random import randint

class Entity(object):

def __init__(self, node):

self.name = None

self.directions = {UP:Vector2(0, -1),DOWN:Vector2(0, 1),

LEFT:Vector2(-1, 0), RIGHT:Vector2(1, 0), STOP:Vector2()}

self.direction = STOP

self.setSpeed(100)

self.radius = 10

self.collideRadius = 5

self.color = WHITE

self.node = node

self.setPosition()

self.target = node

self.visible = True

self.disablePortal = False

def setPosition(self):

self.position = self.node.position.copy()

def validDirection(self, direction):

if direction is not STOP:

if self.node.neighbors[direction] is not None:

return True

return False

def getNewTarget(self, direction):

if self.validDirection(direction):

return self.node.neighbors[direction]

return self.node

def overshotTarget(self):

if self.target is not None:

vec1 = self.target.position - self.node.position

vec2 = self.position - self.node.position

node2Target = vec1.magnitudeSquared()

node2Self = vec2.magnitudeSquared()

return node2Self >= node2Target

return False

def reverseDirection(self):

self.direction *= -1

temp = self.node

self.node = self.target

self.target = temp

def oppositeDirection(self, direction):

if direction is not STOP:

if direction == self.direction * -1:

return True

return False

def setSpeed(self, speed):

self.speed = speed * TILEWIDTH / 16

def render(self, screen):

if self.visible:

p = self.position.asInt()

pygame.draw.circle(screen, self.color, p, self.radius)After that we’re gonna add an ‘update’ method to this class. It’s mostly similar to Pacman’s, except that we’re not choosing the ghosts’ direction. Instead, we’ll make them choose a random next direction when they get to a node.

Like any ‘update’ method, this updates the object’s state as time goes on; hence the ‘dt’ argument to represent time. The ‘self.position’ below that makes the entity move at a constant speed over time. The big ‘if’ statement checks if the entity overshot its target. If it did, per the next 3 lines, its current node is set to be the target, it retrieves the list of valid directions, then it calls to select a random direction.

The ‘if not’ statement deals with portals. Checking if they’re enabled and if the current node has a neighbor connected through a portal. If both conditions are met, the entity’s current node is updated to the neighboring node connected through the portal.

‘getNewTarget’ does what it says. The last ‘if’ statement updates the entity’s direction once the new target is chosen. Assuming the target is different from the current node. Otherwise, if the target is the same as the current, ‘self.direction’ is restricted from changing. Then finally, the entity’s position is updated to the new current node.

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

if self.overshotTarget():

self.node = self.target

directions = self.validDirections()

direction = self.randomDirection(directions)

if not self.disablePortal:

if self.node.neighbors[PORTAL] is not None:

self.node = self.node.neighbors[PORTAL]

self.target = self.getNewTarget(direction)

if self.target is not self.node:

self.direction = direction

else:

self.target = self.getNewTarget(self.direction)

self.setPosition()The ‘validDirections’ method is different from ‘validDirection’ in pacman.py. The former contains a list of valid directions the entity can move in. We use the ‘directions’ variable to initialize an empty list. We’ll loop through all 4 directions and see if the node connects to another node in that direction. If it does, then we make sure it’s not the node we’re coming from. If the list is still empty after those loops, then we stick with the direction from which we came. We add that as the only valid direction.

The second method just chooses one of the directions randomly using the ‘randint’ method we imported.

def validDirections(self):

directions = []

for key in [UP, DOWN, LEFT, RIGHT]:

if self.validDirection(key):

if key != self.direction * -1:

directions.append(key)

if len(directions) == 0:

directions.append(self.direction * -1)

return directions

def randomDirection(self, directions):

return directions[randint(0, len(directions)-1)]Now we gotta add Pacman in as an entity too. This is done in pacman.py

We first import ‘entity’. We change the Pacman class’s inheritance to ‘Entity’. Since we added those generic characteristics in the entity.py file, we can delete them from Pacman so he only has those specific to him. So we’ll delete the methods ‘setPosition’, ‘overshotTarget’, ‘valid/reverse/oppositeDirection’, and the ‘render’ method. Again, these are already in entity.py so it’s redundant to have them in pacman.py too. Also add an ‘Entity.__init__’ line right under Pacman’s ‘init’ method.

import pygame

...

from entity import Entity

class Pacman(Entity):

def __init__(self, node):

Entity.__init__(self, node)

self.name = PACMAN

...Nothing should be different about the game at this point. If it is, you did something wrong

Ghost Setup

Now we’re gonna create a new file ghosts.py. And we’re gonna add a ‘ghosts’ constant with a value of 3.

GHOST = 3Create a ‘Ghost’ class with an inheritance from ‘Entity’. Start the ‘init’ method with an ‘entity init’, setting ‘self’ and ‘node’ as both of their arguments. Write the name and set the points to 200.

import pygame

from pygame.locals import *

from vector import Vector2

from constants import *

from entity import Entity

class Ghost(Entity):

def __init__(self, node):

Entity.__init__(self, node)

self.name = GHOST

self.points = 200We’ll also make our additions in the run.py file. We do the import, and add to the ‘startGame’, ‘update’, and ‘render’ methods.

import pygame

...

from ghosts import Ghost

def startGame(self):

...

self.ghost = Ghost(self.nodes.getStartTempNode())

def update(self):

...

self.pacman.update(dt)

self.ghost.update(dt)

def render(self):

...

self.ghost.render(self.screen)

pygame.display.update()At this point, there is one ghost moving randomly around the maze. Nothing happens if Pacman collides with it

Ghost AI Start

At this point the ghosts are moving randomly around the maze. To make the game a challenge we can give them some intelligence, or at least the appearance of such. We can do this by simply giving them a goal to reach (a vector), and they never have to reach it.

We add a goal vector in the entity.py and the ghosts.py files. Entity’s is set to ‘None’ since that would give all entities the same goal. We just want to work with the ghosts, so we set that in the ghost’s file to specify it.

class Entity(object):

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.goal = None

---SEPARATE FILE---

class Ghost(Entity):

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.goal = Vector2()This next method will take a list of directions, we’ll assume they are already valid directions, and for each of the directions in the list it will calculate the distance from the entity to the goal. It then returns the direction with the smallest distance; specifically the line of sight distance.

What you should see after you implement these changes is that the ghost will be moving around in a circle in the upper left corner. This is because the ghost is basically trying to reach the screen’s origin which is the upper left corner of the screen, but can’t because of the movement restrictions we’ve placed on it. Remember that it can’t ever STOP during the game, so it has to choose a target every time it reaches a node, even if that target takes it further from the goal. But if it is able to choose a target that takes it closer to the goal, it will. In entity.py

def goalDirection(self, directions):

distances = []

for direction in directions:

vec = self.node.position + self.directions[direction]*TILEWIDTH - self.goal

distances.append(vec.magnitudeSquared())

index = distances.index(min(distances))

return directions[index]So for an entity that needs to reach its goal, it’ll call this ‘self.directionMethod’ instead of the ‘randomDirection’ method. It’ll be a variable that replaces it. Also, delete the ‘direction’ variable and replace ‘randomDirection’ with ‘directionMethod’

class Entity(object):

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.directionMethod = self.randomDirection

def update(self, dt):

self.position += self.directions[self.direction]*self.speed*dt

if self.overshotTarget():

self.node = self.target

directions = self.validDirections()

direction = self.directionMethod(directions)

if not self.disablePortal:

if self.node.neighbors[PORTAL] is not None:

self.node = self.node.neighbors[PORTAL]

self.target = self.getNewTarget(direction)

if self.target is not self.node:

self.direction = direction

else:

self.target = self.getNewTarget(self.direction)

self.setPosition()After establishing that, we just tell the ghost to use the new method instead of ‘randomDirections’ in ghosts.py

class Ghost(Entity):

def __init__(self, node):

...

self.directionMethod = self.goalDirectionThe ghost should circle the top left corner at this point.

Modes Overview

Technically, all the phases of the game are based around the ghosts’ behavior. For that, there are 4 modes:

- Chase – the default phase, a ghost is tracking down Pacman; his position is their goal. Different methods for all ghosts

- Freight – when Pacman eats a power pellet, the ghosts are vulnerable and move randomly and slowly. This lasts longer in earlier levels and shorter in the later ones.

- Scatter -a ghost scatters to the corner of the maze. Each ghost has his own corner

- Spawn – when Pacman eats the ghosts. Their goal is to get to their spawn location to respawn. They move very fast in this mode.

We can think of chase and scatter to be the main modes and the others to be transitional. All the ghosts should be synchronized to scatter and chase at the same time. There should be an object to continuously flip these back & forth independent of what the ghosts are doing. The ghosts can individually go into one of the interrupt modes, but once those are finished they can easily find out if they should be in SCATTER or CHASE by asking the main mode object.

We’ll add each of the 4 modes to the constants.py file, numbered 0 to 3 for their values.

SCATTER = 0

CHASE = 1

FREIGHT = 2

SPAWN = 3We’re creating another file called mode.py. Scatter mode has a timer set to it so that when it runs out, it switches to chase mode for however long we set it.

from constants import *

class MainMode(object):

def __init__(self):

self.timer = 0

self.scatter()

def update(self, dt):

self.timer += dt

if self.timer >= self.time:

if self.mode is SCATTER:

self.chase()

elif self.mode is CHASE:

self.scatter()

def scatter(self):

self.mode = SCATTER

self.time = 7

self.timer = 0

def chase(self):

self.mode = CHASE

self.time = 20

self.timer = 0In this file we’re going to create a class that controls the modes so that we can always know which mode the ghost has to be in. Right now it’s only passing along the main mode (scatter or chase).

We’ll also pass in the entity this mode controller is controlling in case it needs to send any messages back to the entity.

class ModeController(object):

def __init__(self, entity):

self.timer = 0

self.time = None

self.mainmode = MainMode()

self.current = self.mainmode.mode

self.entity = entity

def update(self, dt):

self.mainmode.update(dt)

self.current = self.mainmode.modeNow we gotta make the ghosts aware of this mode class. As far as they’re concerned, the only difference between the modes is what their goal (target node) is. As of now, the one ghost’s only goal is scatter, which is defined to the upper-left corner. And since the goal in chase mode is Pacman’s position, we’ll have to make the ghost aware of that.

We first add the import in the ghosts.py file. Then update the ‘init’ method in the Ghost class. Along with the node the ghost should start on, we’ll pass in the Pacman and mode objects. We’ll also create scatter and chase methods so we can replace our goal with the output of the scatter method.

...

from modes import ModeController

class Ghost(Entity):

def __init__(self, node, pacman=None):

...

self.pacman = pacman

self.mode = ModeController(self)We see the scatter and chase methods simply define the ghosts’ goal. Scatter’s is the top-left corner and chase’s is Pacman’s position. In this update method, we’re asking it which mode it’s in. Then we call the parent’s update method at the end.

def update(self, dt):

self.mode.update(dt)

if self.mode.current is SCATTER:

self.scatter()

elif self.mode.current is CHASE:

self.chase()

Entity.update(self, dt)

def scatter(self):

self.goal = Vector2()

def chase(self):

self.goal = self.pacman.positionThen in the run.py file, we pass in the Pacman object to the ghost so he can keep track of where Pacman is.

def startGame(self):

...

self.ghost = Ghost(self.nodes.getStartTempNode(), self.pacman)At this point the ghost should start moving in the top-left corner as before, then eventually start chasing Pacman. Still nothing happens when they collide

Ghost Home

You know what this is. This is where the ghosts start and respawn. Pacman isn’t ever allowed to go in here. Once the game starts, the ghosts don’t come back here unless they’re eaten.

To make the nodes for this, we’re gonna create a new method ‘createHomeNodes’ which will need an x-offset and y-offset. We add this into nodes.py

class NodeGroup(object):

def __init__(self, level):

...

self.homekey = NoneSince the home is so small, we can put the symbols directly in the code instead of a text file.

def createHomeNodes(self, xoffset, yoffset):

homedata = np.array([['X','X','+','X','X'],

['X','X','.','X','X'],

['+','X','.','X','+'],

['+','.','+','.','+'],

['+','X','X','X','+']])

self.createNodeTable(homedata, xoffset, yoffset)

self.connectHorizontally(homedata, xoffset, yoffset)

self.connectVertically(homedata, xoffset, yoffset)

self.homekey = self.constructKey(xoffset+2, yoffset)

return self.homekeyThe nodes of this box have to be other nodes, otherwise the ghosts can’t enter or exit. Pacman should never enter, but the ghosts will need to in spawn mode.

This method connects the topmost node to whatever other node we want. We also need to specify a direction. For example, let’s say there’s a node to the right of the home node that we want to connect to. I need to specify the key to that node and also the RIGHT direction. This will connect the two nodes together in both directions. So the home node will connect to the other node on the LEFT. This will overwrite what was previously in the other nodes’ LEFT value.

def connectHomeNodes(self, homekey, otherkey, direction):

key = self.constructKey(*otherkey)

self.nodesLUT[homekey].neighbors[direction] = self.nodesLUT[key]

self.nodesLUT[key].neighbors[direction*-1] = self.nodesLUT[homekey]In the ‘startGame’ method of the run.py file we’ll add 3 lines to code the home box into actual nodes. We call the ‘connectHomeNodes’ method twice so the home is connected to a node to its left and right.

def startGame(self):

self.nodes.setPortalPair((0,17), (27,17))

homekey = self.nodes.createHomeNodes(11.5, 14)

self.nodes.connectHomeNodes(homekey, (12,14), LEFT)

self.nodes.connectHomeNodes(homekey, (15,14), RIGHT)