In chapter 10 of CODE, it starts off with a brief overview of logic, per Aristotle’s theory.

Basic logic is built on syllogisms. This is the standard three-sentence formula for how we arrive at the truth of a matter.

There is a major premise, a minor one, and a conclusion.

The most common one you’ve probably seen is,

- All men are mortal

- Socrates is a man

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Many mathematicians have attempted to understand logic using all the numbers and symbols at their disposal.

That all changed with George Boole, who you may recognize from the boolean operators in algebra.

A self-taught man from a poor background, Boole inserted himself into academia by publishing a series of papers that were lauded by the local institutions of the time. He observed that if humans use logic in the same manner that we use math, then we can use math to better understand the mind; ultimately make better decisions. That hypothesis is a little reductive, but I see the idea he was aiming for.

Boolean algebra is the arithmetical form of logic that we’re used to.

Example straight from the book: Anya has 3 pounds of tofu, Betty has twice as much tofu as Anya, Carmen has 5 pounds more tofu than Betty, and Deirdre has triple the amount of tofu that Carmen has. So how much tofu does Deirdre have?

Now it shouldn’t be hard to do this in our heads, but that isn’t going to get us far.

I remember back in middle school, there was a math class assignment I had to do. So I did it, I got the right answer….. yet the teacher told me I was wrong.

So I started to argue with him, “How is it wrong if I got the right answer?”. He didn’t have any other response besides, “It is not the right way”.

Of course I started to get irritated. I kept asking him the same thing, “HOW IS IT WRONG IF I GOT THE RIGHT ANSWER?”, and of course he kept with his simple-minded response. So in the end, I got the problem wrong.

What I did wrong was doing it all in my head; I didn’t show my work.

Now that I’m older (or just learning to actually use and not just pass), I can see why this was wrong, even though I still resent that teacher for not doing his job and teaching me wtf I was doing wrong, but I digress.

See, doing math in our head is only good for simple algebra, like our tofu problem, but when it comes to dealing with multiple variables and decimals, that method falls apart quick.

This is one of those situations where both sides were right and wrong in their own way, but I will continue to hold that grudge against the teacher since he was the supposed superior who failed to live up to his duty.

So on one side, the teacher was wrong for refusing to explain why we need to show our work. On the other side, I was wrong for thinking I can get by doing all algebra in my head.

As someone who aspires to work in science, I do see why it’s necessary to show our work, but the teacher shouldn’t have made me out to be wrong even though I got the correct answer.

Apparently it was the worst thing in the world for him to simply explain, “Look, you did get this problem right, but you can’t rely on doing it in your head. Algebra in the real world requires you to show your work, and you can’t do that if you don’t write anything down. So again, you did get this problem right, and it is good that you can do it in your head, that will come in handy in life, but you have to focus on showing your work too.”

But nah, we can’t expect our ‘qualified’ educators to articulate themselves that well.

Anyway, enough reminiscing. Back to our tofu problem.

You might’ve noticed the names in the problem are our first four letters, (A)nya, (B)etty, (C)armen, (D)eirdre, which will make our translation to arithmetic smoother.

A = 3

B = 2 x A

C= B+5

D = 3 x C

So our ultimate goal in arithmetic is to simplify our equations; we want to get them into as few numbers as possible while keeping all the variables present.

D = 3 x C

D = 3 x (B+5)

D = 3 x ((2 x A)+5)

D = 3 x ((2 x 3) + 5)

D = 33

Properties of Numbers

Adding and multiplication are commutative; the answer is the same regardless of their order.

A+B=B+A | A x B=B x A

By contrast, this means that subtraction and division are not commutative, since their order is relevant.

We also have associative. If we have A+B+C, the equation will essentially be the same as A+(B+C) or (A+B)+C.

Multiplication is distributive over addition. I always found this one to be the easiest. It’s just when we multiply the separate numbers by each individual number in the parentheses.

A x (B+C)=(A x B)+(A x C)

Boole’s Way

Our man Boole was able to detach algebraic expressions from strict numbers. We typically call them variables, but they are actually classes. Classes are nested within sets.

The book uses the example of cats, so let’s establish the sets and classes of cats.

First we got male (M), and female (F); like there’d be anything else. For colors, we got tan (T), black (B), white (W), and other (O). And just to add one more set, we got neutered (N) and unneutered (U).

Now with numbers, we’re used to seeing addition as combining addends. In this abstract Boolean algebra, + means a union (∪) of classes. While x means an intersection (∩) of classes.

So B+W (or B∪ N) would represent the class of all cats that are either black or white.

As for multiplication, and there’s a slight nuance in this, B x W (or B∩W) would represent the cats that are both black and white.

So unions are either-or, and intersections are both or all.

Boolean algebra uses 1 to mean all, and 0 as none.

The class of all cats would be: M+F=1 | B+W+T+O=1 | N+U=1

We can also use it to exclude: 1-M=F (All cats except males; only females)

0 in this context would be M x F = 0, since there are no both male-female cats

F+(1-F) = 1 (All female cats – all cats except females = all cats)

F x (1-F) = 0 (All female cats x all cats except females = no cats)

To go back to the syllogism, “All persons are mortal (M). Socrates (S) is a person (P).”

P x M = P (Persons x Mortal = ALL persons)

We couldn’t do P x M = M because that implies that only persons are mortal; it doesn’t account for animals and plants

So we know that Socrates is a person, meaning S x P = S

Now let’s put this together

S x (P x M) = S

By associative law, this is the same as (S x P) x M= S

But since we know that S x P = S (and we know that persons are mortal), we’ll just simplify it with

S x M = S

If he wasn’t mortal, it’d be S x M= 0

We couldn’t do S x M = M because, like for persons, Socrates is not the only mortal being in existence.

So we use Boolean algebra as a model for worldly logic. Every decision we make is arrived at by applying logic to set criteria.

Remember that a union (∪ or +) means OR, an intersection (∩ or x) means AND, and 1- means NOT

Here’s a more practical example:

I walk into a pet store, and tell the salesperson,

- “I want a male cat, neutered, either white or tan

- OR a female cat, neutered, any color but white

- OR I’ll take any cat as long as it’s black”.

That request in Boolean algebra would look like:

(M x N x (W + T)) + (F x N x (1 – W)) + B

In word form, this looks like:

(M AND N AND (W OR T)) OR (F AND N AND (NOT W)) OR B

Boolean Test

Now we’ll go into the binary-form of algebra.

Similar to binary code like we glazed over last post, only 1 and 0 is used in this form. In this case 1 means TRUE and 0 means FALSE.

Mind you, this is not another way of writing down the request like we just did. This binary form is used to test the request.

So to bring the expression back down:

(M x N x (W + T)) + (F x N x (1-W)) + B

Let’s say the salesperson first brings out an unneutered tan male. Applying that to the Boolean test would be:

(1 x 0 x (0 + 1)) + (0 x 0 x (1 – 0)) + 0

The only 1’s in this expression are ‘male’ and ‘tan’ since those were the only met criteria. Since this cat is unneutered, it does not meet the criteria, therefore it is not a valid option for me (the buyer).

In line with regular math, only 1 x 1 = 1; all parts must be satisfied before the criteria is fully met. A 0 anywhere in that equation would invalidate it, since it represents a part of the criteria that was not met.

Although, 0 can be present in any OR (union) expressions since it doesn’t mean it has to be a part, it only can be; has the potential to be, though not currently is.

If I ask for either a red OR blue ball, and you bring me one red and one green, my criteria was still satisfied, because I don’t have to take the green one. I already have an option that suffices (the red ball).

1 + 0 = 1 | 0 + 1 = 1

Circuitry

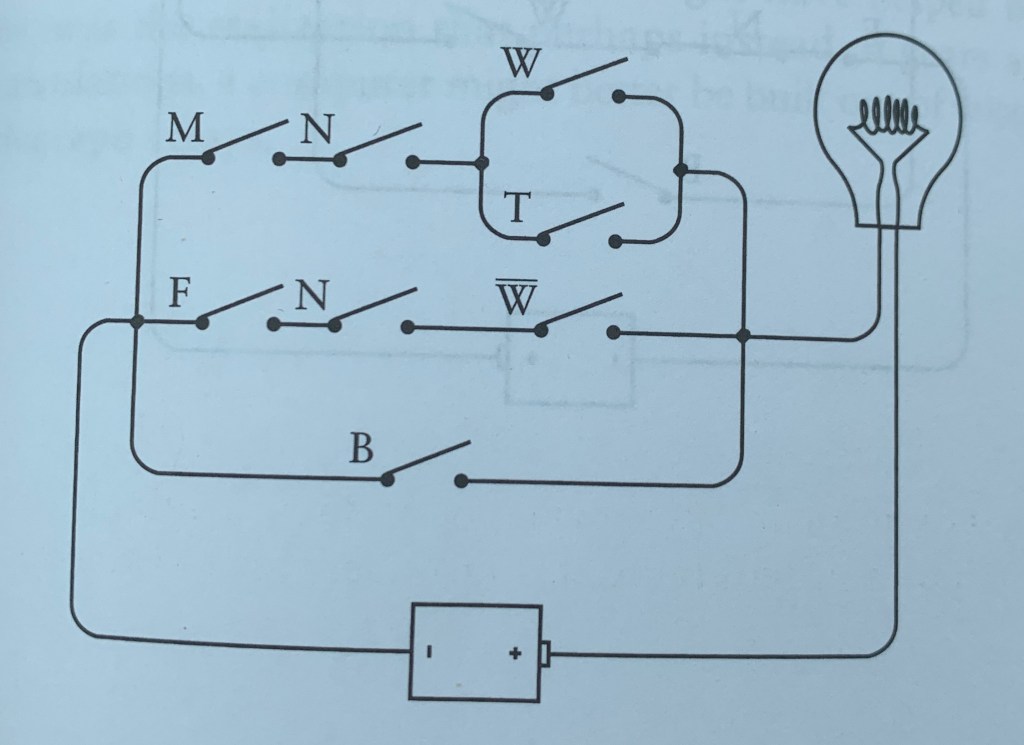

To close out the chapter, let’s apply Boole’s way to the makeshift lightbulb circuit we did a while ago.

To refresh, a circuit is made of a lightbulb connected to a battery through a switch. For this example, we’ll use 2 switches in series; meaning they must both be closed for the current to travel.

So since both switches in series must be closed to light the bulb, that makes this an AND (x or ∩) situation.

On the other hand, we can arrange the switches parallel to each other (one above the other as compared to right next to each other). That arrangement is an OR (+ or ∪) situation.

I’m not doing a complete elaboration on it, but here’s a diagram of a circuit with our cat-shopping situation applied to it. It shouldn’t be hard for you to translate it from the expression to see what’s needed to light the bulb (buy the right cat).

Chapter 11

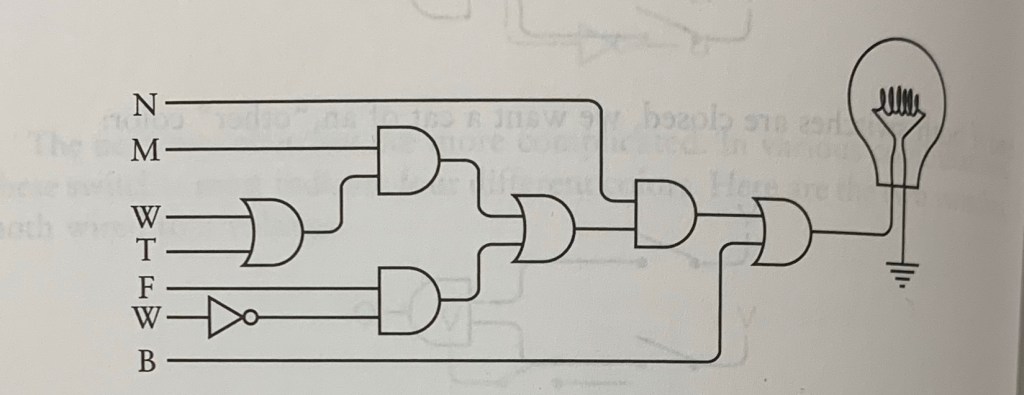

Relating to the diagram we just looked over, a circuit has a series of logic gates. They serve the same exact function as an actual gate, to restrict access to anything and to allow it for certain things.

An inverter, simply put ensures that when one gate is opened, the other is closed. If male and female are in series with one switch, without the inverter, both would be lit, which is impossible. I’m not entirely confident in this explanation. I’ll cross my fingers that it’ll make more sense later.

4 AND gates with 2 inverters is a ‘2-Line-to-4-Line Decoder.’ There’s also a 3 to 8, a 4 to 16, and so forth. We’ll come back to this in a later post.

Putting it Altogether

Rd yall, if we can get past this, the rest of the book should be a breeze. Let’s just take it step by step.

Since this is using an electrical circuit as the model, I’ll take us through this by tracking how our logical current (LC) makes it way through the circuit.

- The inverter symbol is the triangle with the dot; next to the second W

- The flat plug represents AND

- The curved plug represents OR

- The wires going in the plugs from the left are the inputs, and those coming out on the right are outputs

So let’s bring our expression down again

(M x N x (W + T)) + (F x N x (1-W)) + B

Let’s get the easy one out the way first: anything as long as it’s black.

We see the B (at the bottom) only goes through the last OR plug, who shares a wire with N. This makes sense because if the cat isn’t black, the only other absolute requirement is that the cat is neutered.

Now just behind the last OR plug, we see the AND plug, but let’s put that to the side for now and look at the OR plug behind that.

This OR plug (the one smack in the middle) is for ‘male’ or ‘female’. So we know that as long as one of those are satisfied, it can move onto the last AND plug.

Take it from the beginning now, from top to bottom. Say the salesperson brought out a neutered female, any color but white (F x N x (1-W)):

- We know it’s neutered, so N’s LC will go through

- It’s not male, white, or tan, so we disregard those; no LC

- We know it’s female, so F’s LC is good

- Now this second W below the F has an inverter, which reverses the LC. It’s best if we just look at the inverter as if it’s on a chronic opposite day; whatever function is next to it, choose the opposite of it. So as long as the cat is any color but white, that triggers this second W’s LC.

Since this cat fits what we’re looking for, this bulb is lit (kitty has a new home!)!

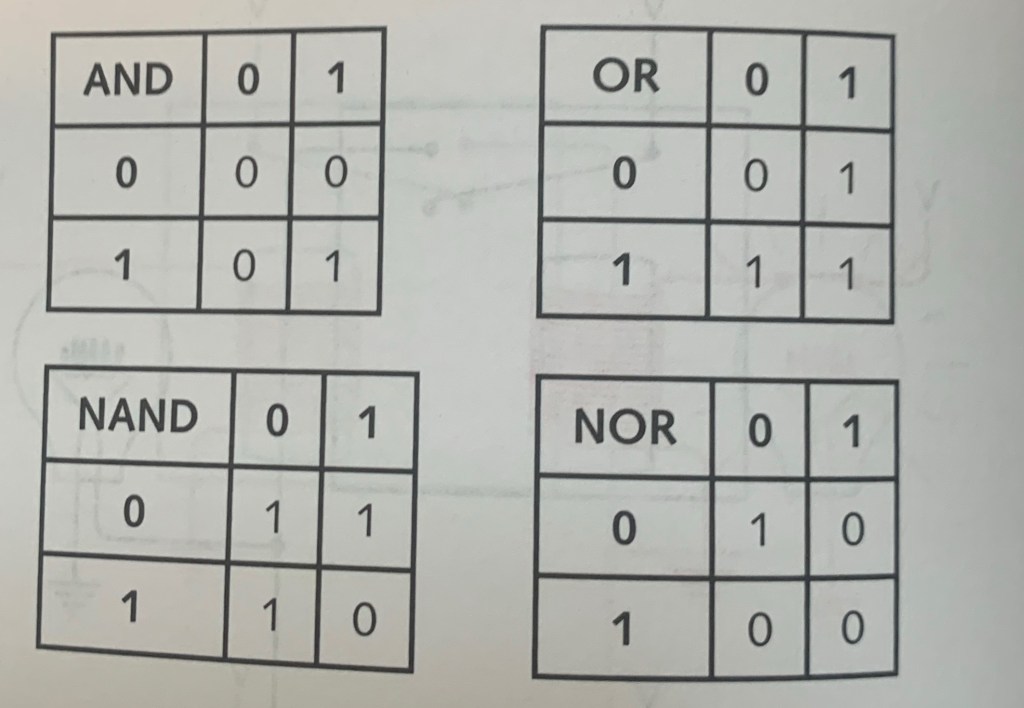

The NANDS NOR the AND OR NOTS

Similar to the inverters, AND and OR have their own antitheses, NAND and NOR.

AND = only both | OR = either one, but never none | NAND = anything but both | NOR = none

NOR looks redundant, like boneless watermelon. I get the concept, I just don’t see the full purpose of these yet.

I skipped over a lot in this chapter, I just wanted to put the symbols on paper so we can get ready to push through the rest of this book. The next chapter goes deeper into binaries, but we surely will be seeing more of these circuits soon.