This content is based on the book ‘CODE’ by Charles Petzold.

Modern number system is derived from the Hindu-Arabic. Developed by Indians, but presented by Arabics to the Europeans.

It’s positional (per the book, I like ‘linear’ better), where the numbers are in a digit matter just as much as what they are. Obviously 4023 isn’t the same number as 3240.

It doesn’t have a special symbol for 10, like other number systems. This gives it the simpler alternate names of ‘base-ten’ or just ‘decimal’.

But is uniquely the only system to have 0.

10 is our sacred ‘whole’ number, which our fingers and toes made convenient.

One alternate number system is octal, or ‘base-8’. Some ancient civilizations used this system given they would count either their knuckles or the spaces between their fingers.

This weird system believes in counting: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

Yes. 8 and 9 do not exist in the octal system.

I’m seeing that this isn’t commonly used today, compared to the binary (base-2) and hexadecimal (base-16) systems, but I’ll still learn its basics for the sake of getting used to a new system.

8 in regular decimal (written as 8TEN) = 10 in octal (written as 10EIGHT)

Remember, there are no 8’s or 9’s in octal. It gets tricky once we go up.

15TEN = 17EIGHT

16TEN = 20EIGHT

18TEN = 22EIGHT

23TEN = 27EIGHT

24TEN = 30EIGHT

If you got a high-10s number, it’s much easier to just go through your multiples of 8.

8TEN = 10EIGHT

16TEN = 20EIGHT

24TEN = 30EIGHT

32TEN = 40EIGHT

40TEN = 50EIGHT

And so on.

Binary

This should be a little more comfortable. Not ‘easier’, just more familiar since this is used more in computer science.

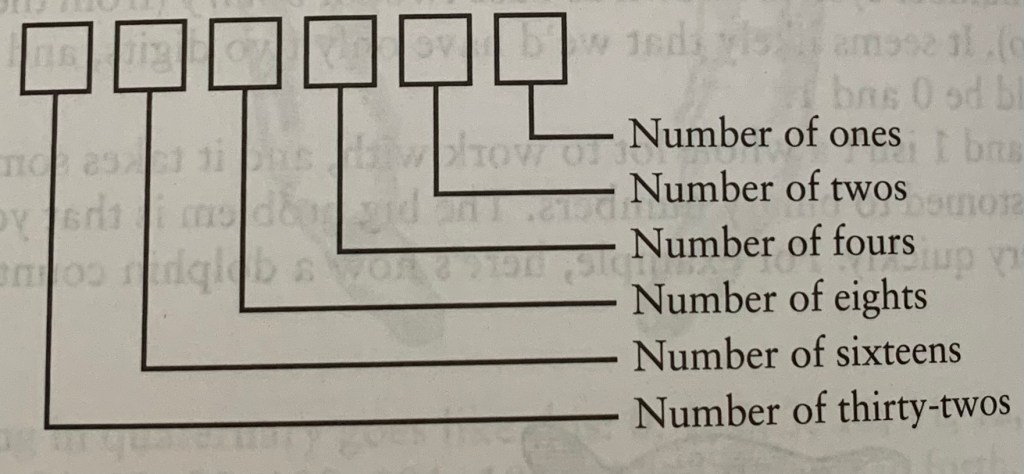

To refresh, ‘bi-‘ means 2, so binary is based on 2 digits (hence ‘base-2’), 0 and 1.

Starting off, 1TEN = 1BI

2TEN = 10BI

3TEN = 11BI

4TEN = 100BI

So each binary number will either end in 0, 1, 10, or 11.

Binary can also be used for alphabetical letters too, but we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it. Try using the digit structure to find the binary counterparts to decimal numbers.

In tech jargon, the word ‘bit’ is used to mean a binary digit, or more broadly, a basic building block of information. Bits are the smallest (in size, not importance) unit of information.

“Information represents a choice between two or more possibilities“

The rest of the chapter takes you through a variety of devices that use ‘bit’ information. Using lanterns, movie ratings, film speeds, and barcodes, the ultimate purpose of a bit is to convey information in as small a unit as possible.

For UPC barcodes, the information is represented by vertical lines that vary by width and the space between the lines. UPC doesn’t have a cut-and-paste formula like other bits, yet its visual representation looks similar to morse code.

What I Learned Today

- Octal number system

- Binary number system (basics)

- What a ‘bit’ is and a few examples of how it plays out in real-life devices

I know I glazed over a lot when it came to explaining the bits and how to count them when it comes to longer series (one line on a UPC barcode could represent a 7-digit binary number), but I’m glad I got a basic overview of how these numbers systems work. Binary looks exhausting as the numbers get higher, but I’ll have to get used to it if I plan on working with computers. I should probably start memorizing its formula so I can instantly translate a decimal into its binary counterpart.

One thought on “Computer Science #2: Alternate Number Systems”